The first post on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) focused mostly on the anatomy of the knee joint and how injury occurs there. This second part will look at treating one, from a sports physiotherapist point of view.

Conservative or Surgical:

- Often both methods are required

- Depends upon:

- Age of athlete

- Degree of instability

- Associated injuries

- Pivoting in sport

- Compliance with rehab programme

- Basically, is it worth the surgery? It’s a long lay off for ACL injuries in terms of rehab, and if you’re just playing football on a Sunday morning with your mates, you may have to consider whether a lengthy rehab plan is worth it.

Surgical Treatment:

- People will often say that it gives way – the knee is trying to slip out of place due to no ACL and that puts the meniscus at risk and can lead to joint degeneration.

- Aim is to replace the torn ACL with a graft that reproduces the normal function of the ligament. You cannot repair the ACL, it would be like trying to repair a piece of string.

- Surgery options:

- Bone-patella tendon-bone; this gives a chronically sore knee so bad if you need to kneel a lot

- Hamstring graft; doesn’t anchor as well and is quite thin so you can double it up to make it less stretchy

Problems:

- Patella tendon reconstruction is associated with pain on kneeling, a higher rate of morbidity and a big scar.

- Hamstring reconstruction is associated with decreased end range knee flexion power.

- If a hamstring graft is done then you almost must ensure this muscle goes through rehabilitation too.

- Often methods depend on surgeons and countries. Some countries they will use the hamstring from the injured leg, whereas others prefer to take it from the non-injured knee. There’s no right or wrong option here either.

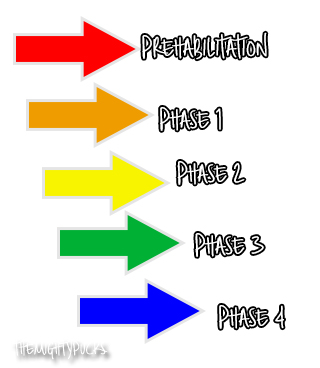

The next half of this post will go over a general rehab plan for ACL injuries.

Accelerated Rehabilitation:

- Prehabilitation

- Reduce swelling/pain, restore FROM and educate the athlete. This can be walking, cycling or easy front crawl in a pool. Surgeon will not operate until injury site is ready with ROM and effusion has stopped. Talk to player, reason with them and explain why the operation cannot be performed immediately. PRICE and movement are key. More you move, the quicker the swelling goes down.

- Phase 1 (0-2 weeks) Post-Op

- Partial/full weight bearing, or functional brace could be worn. Aim to reduce swelling and get 0-100 degree movement range. 5/5 hamstring and quads strength. Start with simple exercises and build up; quads, VMO, bilateral calf raise, hip adduction and extension, hamstring pulleys, gait drills.

- Phase 2 (2-12 weeks) Post-Op

- No swelling, full flexion 130 degrees and full hyperextension. Full squat ability and good balance with unrestricted walking. ROM/quads, mini-squats and lunges, leg press, step-ups and exercise bike.

- Phase 3 (3-6 months) Post-Op

- Full ROM/strength. Return to jogging/agility. Restricted sport specific drills. Straight line jogging, road bike, jump and land drills, agility drills.

- Phase 4 (6-12 months) Post-Op

- Progressive return to sport, restricted then unrestricted training. Partial match play then competitive match.

- Must do skill work too – practice kicking balls if they’re a footballer.

Outcome Measures:

- Return to sport

- Re-injury rate

- Prevalence of osteoarthritis